This is a story about some encounters I had nearly 20 years ago in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo, while researching my dissertation on transnational migrants from the western Sahel. It was in Brazzaville that I got to know a Malian named Malik, who one day asked if I’d heard of Amway, the U.S. network marketing company. He invited me to attend one of its sales pitch meetings at a local home. Malik had recently signed on to sell Amway products, and he wanted me to hear about them from the fellow who had recruited him. What follows is a tale of desperation and hope, capitalism and power.

It seemed an unlikely setting for a modern capitalist enterprise: inside a packed earth courtyard, three wooden benches and a few shaky plastic chairs were perched under a tattered tarpaulin. I sat with a dozen Malian men whom Malik had brought while a few others stood nearby pretending not to be interested. Behind us, women tended to cooking pots amid the occasional squawking of chickens and noise from a couple of carpenters.

Jean-Luc, the presenter, was a Congolese man in his thirties. He wore a wax-print shirt and pinstriped trousers, and used a whiteboard and green magic marker to underscore his points. He liberally dosed his spoken French with English terms like “business” and “independent business owner” (or “eye-bee-oh,” with the letters pronounced in the English fashion). Jean-Luc also dropped names of wealthy men like McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc, who featured in a promotional video many attendees had already seen.

The core message of Jean-Luc’s sales pitch was financial freedom–what it means and how to achieve it. You can’t get there by working for somebody else or even self-employment; there aren’t enough hours in the day, and you’ll be constantly beset by risk and bothered by government regulations, customs fees, and taxation. The only way to achieve financial freedom in this era of globalization, in the information age, is to duplicate your time so that you are earning money even when you’re asleep. Every hour without any remunerative activity is a missed opportunity. Jean-Luc illustrated this point by telling us about a distributor who was shot by jealous friends and spent three months hospitalized in a coma; when he emerged he was already at the next level because his network had been working for him the whole time. And so we learned about network marketing, value points, and the advancement ladder from IBO to Silver to Platinum to Emerald (commission: 9 million CFA francs/month) to Diamond (commission: 100 million francs/month). The latter stage would enable you to attend Amway conferences in the U.S., with all expenses paid and a limo to pick you up from the airport.

Next, Jean-Luc turned to the products. The Amway line was divided into different brands for skin care products, dietary supplements, and home goods. Jean-Luc’s claims for these products were wildly overstated: ginkgo biloba is a miracle drug; bilberry and selenium-E can cure sterility; this special toothpaste will eliminate cavities and toothaches. This last claim provoked an objection from one attendee: “Someone just the other day said he bought that toothpaste from Malik but it didn’t do any good, and he wanted his money back.” We’ll get to questions at the end, Jean-Luc said without missing a beat, and carried on describing company products. (In the event, the objector had to leave before the presentation ended, and nobody brought up the topic of product performance again.) Everything Amway sells is made from nature, Jean-Luc assured us, and all of these artificial foods we’re eating are the reason why we’re having so many unnatural problems—deformed babies and c-sections and other things. He made certain to point out that Amway’s products were not medicines and could not be regulated as such.

To become an entry-level distributor (you’re considered an “independent business owner,” not an employee of the company), one had to sign a contract and pay 84000 francs–about US$160–for the franchise rights. I asked Jean-Luc how many people belonged to the Amway system in Congo; he replied that they’d only been working there for a few years and already had a few thousand distributors, including one Silver and one Platinum. After Jean-Luc wrapped up his spiel, Malik explained the multilevel business plan and the value point reward system in Bamanan for the benefit of audience members who didn’t seem to have grasped these details. The meeting broke up after an hour with nobody visibly sold on the plan.

I, however, had become curious about the company’s Congolese distribution. According to Amway’s website, there was no official branch in the country and the company did not authorize the distribution or sale of its products there; I emailed someone at the company and received confirmation of this. Malik had also shown me an English-language manual in which I read that it was strictly against company policy to sell Amway products in any country in which Amway had no official branch. So how were these Amway products getting to Congo? What had Jean-Luc meant when he said that Congo was part of South Africa’s network?

I put these questions to Malik a few days after we attended the sales pitch. Well, Amway may not be doing business in Congo now, he acknowledged, but once they generate enough business here and someone achieves Diamond status, the company will come and set up its own factories, warehouses, and delivery system. But how could Amway do that, I wondered, if its products weren’t supposed to be sold in Congo in the first place? I doubted that even Malik believed his own rationale.

Eventually I heard something revealing about the distribution network. A wealthy Congolese entrepreneur who did business in South Africa had registered as an Amway seller there. He was said to be ordering his products from South Africa and then transshipping them to Congo without the company’s knowledge. He was also a colonel in the Congolese armed forces and could avoid paying those pesky customs fees. (That’s how things worked in Congo in those years following the country’s civil war: whatever was happening–a new enterprise, an apartment building going up, a freshly formed athletic association–there was always a colonel connected to it somehow.) So any contract signed by a new “independent business owner” in Brazzaville was with the colonel, not Amway, and would be enforced by the colonel’s friends in the security services. Jean-Luc, Malik, and others were using their time and networks to add to the colonel’s riches, and would never be rewarded by the company for doing so.

Malik was undeterred by this information. As long as the government and the company didn’t find out, he reasoned, then there was no harm being done, and some people were making money out of it. One way or another, Malik hoped to get his piece of the network marketing action. I never did manage to talk him out of working for the colonel. But the episode taught me how the economy worked on illusions and threats.

Postscript: All these years later, among the scores of countries in which Amway officially sells its products, South Africa remains the only one on the African continent. But I suspect that Amway products and sales pitches are still being sold in Brazzaville, and wherever the allure of profit is stronger than official company policies and government regulations.

I ni ce, karamɔgɔ! Enjoyed this piece/write-up from your archives 😉

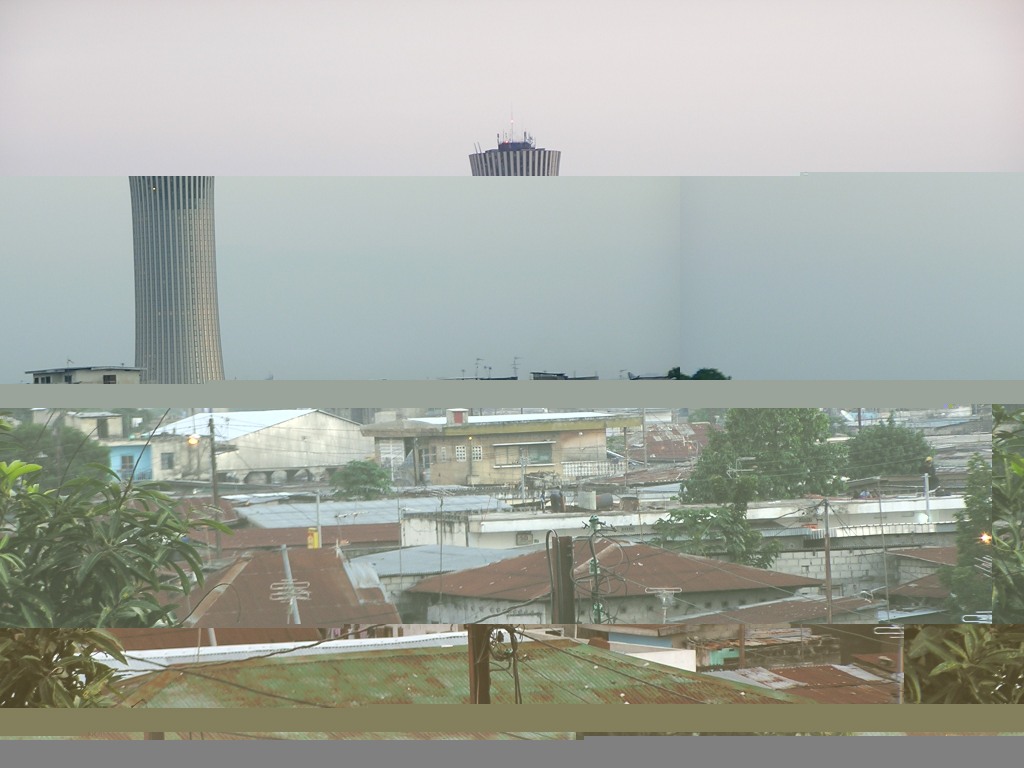

Nice pics!

Not much worse than any other of the zillion scams going on in Afrique.

Makes me think of Achille Mbembe or Appiah or others ranting about western values.