Mali is a land of rich cultural diversity, this much is certain. The country’s population comprises dozens of ethnic and language groups, from Khassonke in the west to Bwa in the east, and from Tuareg in the north to Senoufo in the south. Malians practice multiple modes of subsistence, most notably agriculture and livestock herding but also fishing, hunting, and other types of foraging. It is admirable that Malians get along as well as they do, despite–or perhaps because of–their differences.

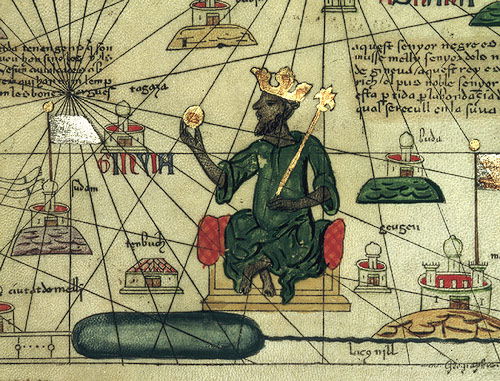

A viewpoint especially common among Malians themselves is that the necessity of navigating cultural difference has made Malian society unusually harmonious. Over the past thousand years, Malians incorporated people of all walks of life into their communities. They developed the famous senankunya system of joking relations that continues to this day to knit together people of various ethnicities, clans, and castes. They promoted dialogue and nonviolent resolution to conflict. Oral historians, bards and musicians–those jeli or griots of global renown–used their prodigious talents to smooth over disputes and forge a shared identity. Gaining its independence in a world wracked by communal violence and exclusionary nationalism, Mali constituted an exception. (See Aida Grovestins’ article in The Guardian for a recent invocation of this narrative, one that surely warms the hearts of military leaders throughout the region.)

I certainly believe the rest of the world has something to learn from Mali’s example. In early 2013, as French troops were still spreading out across Malian territory as part of Operation Serval, I wrote that Mali was blessed with four special cultural institutions: in addition to senankunya mentioned above, I singled out an extraverted form of personhood (mɔgɔya, in Manding), a particular understanding of dignity (danbe), and strong patriotism (faso kanu). And I called on Malians to harness these institutions to create a more inclusive society. “It is not so far-fetched to imagine,” I wrote, “that all citizens of Mali, regardless of ethnicity or skin tone, might someday soon unite behind a common national identity.”

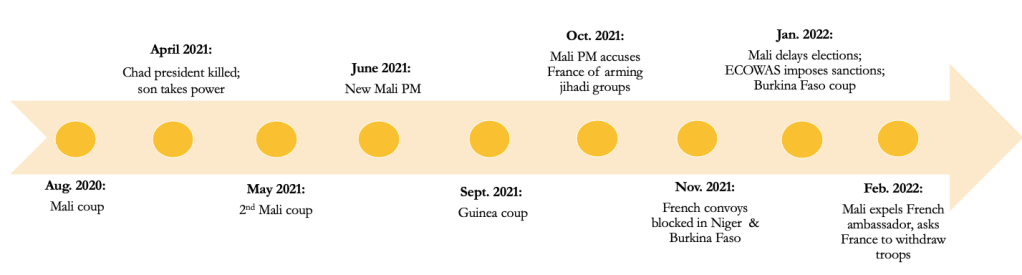

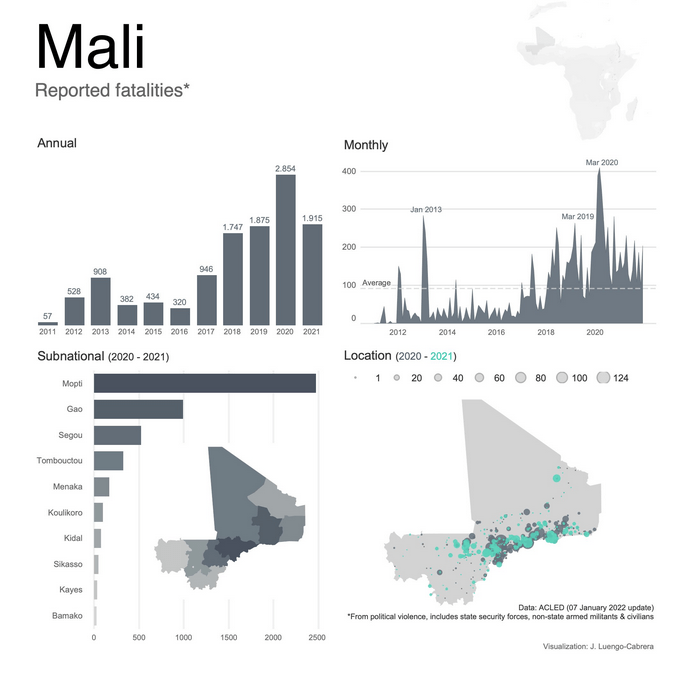

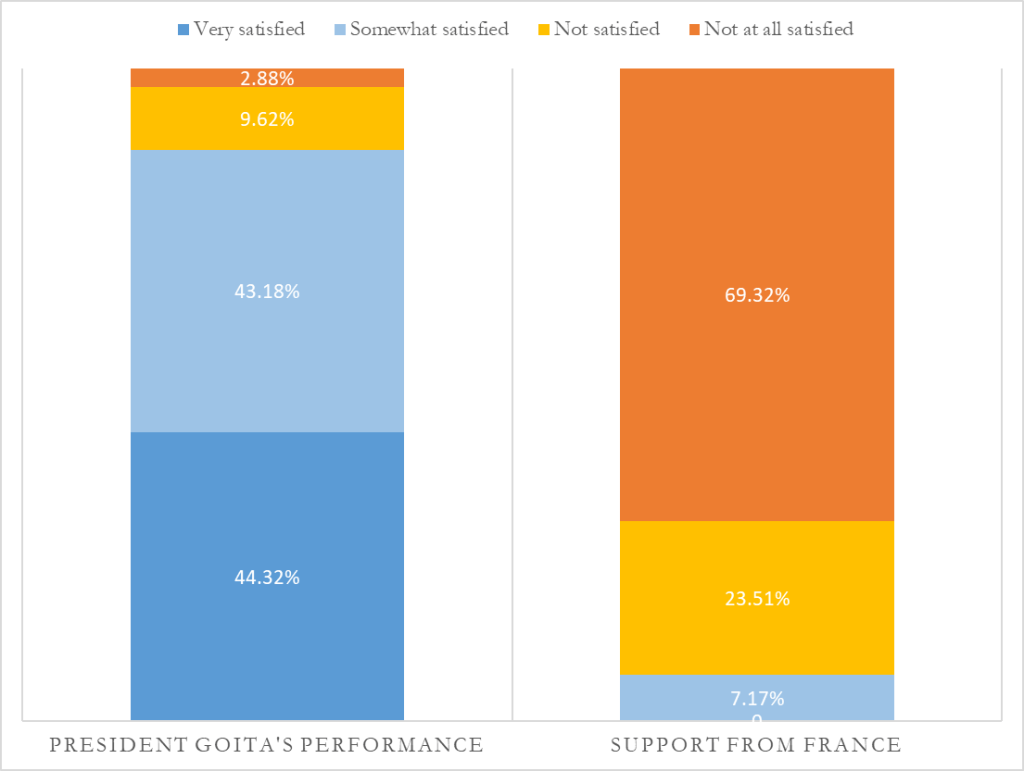

But twelve years later, my faith in the power of Malian exceptionalism has dimmed, less due to the persistence of conflict than to the steadfast refusal of so many in Mali to acknowledge conflict’s local roots. To be sure, instability in the country and the wider Sahel is linked to global forces, most notably NATO’s military campaign in Libya and the harmful approaches taken by the UN and the French military. The past several years, however, have shown that much of the problem lies with the postcolonial state itself and the nature of its institutions.

Malians who claim that the country’s Fulani and Dogon communities used to get along have a point: massacres of entire villages, such as those that have struck the Mopti region since 2019, are a new phenomenon. That being said, conflicts between herders (Fulani or Tuareg) and farmers (Dogon, Bambara and others) also have a long history in Mali. As research over the past decade (by Benjaminsen & Ba, Jourde, Brossier & Cissé among many others) makes clear, such conflicts have increasingly been fueled by internal status hierarchies and the predation of government courts and security forces. Mali’s military authorities have not tackled these problems. Instead, their propagandists spread the falsehood that the insurgents attacking villages and army bases are actually foreign mercenaries. (I have long been fascinated by this desire to see mercenaries everywhere except where they actually are.)

Mali’s leaders like to say that their country is free of ethnic conflict and discrimination. Tell that to the 140,000 Malian citizens who have fled the country to take refuge in neighboring Mauritania. Aided and abetted by Russian troops, the Malian military has driven tens of thousands of Fulani and Tuareg civilians from their homes. Once across the border in Mauritania, they recount harrowing stories of indiscriminate violence. “If you’re Fulani, they’ll shoot you on sight,” one refugee says. Particularly since 2022, these bloody counter-insurgency campaigns have left the ideal of an inherently peaceful, dialogue-centered Malian society in tatters.

It’s been said that a nation is a society united by delusions about its ancestors and by common hatred of out-groups. What if part of Mali’s problem lies in its national mythos, focused overwhelmingly on the exploits of sedentary agriculturalists speaking variants of the Manding language? What room remains in this vision for nomads, for pastoralists, for members of ethnic out-groups? Having spent two years in a Senoufo-speaking village, I can tell you that the state’s Manding-centric orientation leaves many people (even in the south!) feeling excluded. Out-groups must be made into in-groups without losing their distinctiveness.

The thing about wars–even so-called “culture wars”–is that they’re not driven by culture. While they may express themselves in the language of identity, they are always waged for other reasons. Different groups do not fight merely because they are different; they fight over power, over resources, over land and water and grazing rights. To resolve or prevent such fighting requires inclusive institutions capable of holding wrongdoers accountable, standing up to powerful actors, and promoting equality under the law. These institutions are essential for mediating between the various interest and status groups that compose Malian society. By all appearances, Mali’s modern state does not have enough such institutions. All the art festivals, joking relations, and regional alliances under the sun cannot make up for this deficit; only the slow, hard work of politics can do it. This is the very work that Malian authorities have been actively suppressing, even as they stockpile weapons and promote exclusionary versions of Mali’s national origin story.

Malians are all too familiar with their state’s failings. That these failings have helped sustain and intensify their country’s ongoing insecurity should be obvious. This recognition requires the will to push back against nationalist dogma claiming that “all our ills come from beyond our borders,” and that may be what Mali’s leaders fear most. But to survive and thrive, the Malian nation requires this will. Despite the tragedies of the last several years, I still want to see peace restored in a Mali that can realize its people’s exceptional potential.