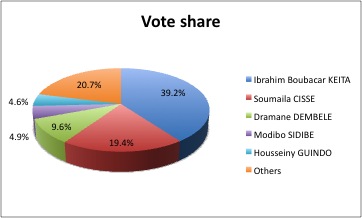

The results are finally in, after five days of nervous expectation. The Ministry of Territorial Administration has released its official vote tally from the 28 July first round of presidential voting [PDF]. Since the ministry, in its inimitably opaque fashion, arranged these results in no discernible order, I have organized my own complete ranking of candidates by vote share [PDF]. The chart below shows only the top five finishers from that ranking.

To nobody’s surprise, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita is well out in front (see my in-depth profile of “IBK” on Think Africa Press). He will face Soumaïla Cissé in the 11 August run-off. Both are established career politicians. This year’s crop of “reform” candidates didn’t fare so well: Moussa Mara finished in 11th place, Soumana Sako in 13th, and Yeah Samaké in 16th. The latter’s finish was behind even that of Oumar Ibrahim Touré, a man so “old guard” that his claim to fame is having run Mali’s health ministry at a time when millions of aid dollars notoriously disappeared from its coffers.

To nobody’s surprise, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita is well out in front (see my in-depth profile of “IBK” on Think Africa Press). He will face Soumaïla Cissé in the 11 August run-off. Both are established career politicians. This year’s crop of “reform” candidates didn’t fare so well: Moussa Mara finished in 11th place, Soumana Sako in 13th, and Yeah Samaké in 16th. The latter’s finish was behind even that of Oumar Ibrahim Touré, a man so “old guard” that his claim to fame is having run Mali’s health ministry at a time when millions of aid dollars notoriously disappeared from its coffers.

It’s worth pointing out how closely these results conform to Sidiki Guindo’s poll from 12 weeks ago, featured on this blog in May. Mali’s “lone pollster” correctly predicted not only the order of the top three candidates, but also the level of support for the top candidate. His follow-up poll from July was even more accurate. Bravo, Sidiki!

Was Mali’s election too big to fail?

Well before these results were even hinted at, the first phase of Mali’s presidential election was being hailed as a shining success. The country’s interim president wasted no time in describing it, shortly after voting began Sunday morning, as “the best election that Malians can remember since 1960.” Governments abroad had the decorum to wait until after polls had closed to give their endorsements. France’s Foreign Ministry issued a statement the next day welcoming “the good conduct of the Malian presidential election, marked by heavy turnout and the absence of major incidents” [PDF]. The US State Department commended Malian authorities for their “commitment to holding transparent, inclusive elections.” African Union and Mali’s neighbors have added their own seal of approval. If observers witnessed “minor technical difficulties” and “irregularities,” it was nothing to cast doubt over the poll’s inclusiveness and credibility.

Or was it? Malians’ perspective depends in part on where they live, and which candidate they support. Disorganization prevented many living outside the country from casting ballots. Election day for France’s Malian community was described as a “big mess.” In the Parisian suburb of Montreuil, election officials were chased out of one polling place by Malian residents angered over not receiving their voter ID cards; the vote in that neighborhood was effectively boycotted. In refugee camps in Burkina Faso, only about a hundred of 3500 Malians registered were able to cast ballots. In Bamako confusion was also widespread, as many would-be voters couldn’t find their polling stations. Reports posted by members of the public to the SOS Démocratie website enumerated dozens of instances of absent poll workers, insufficient voting materiel, and chaotic electoral lists. They also made allegations (unconfirmed, but plausible) of vote-buying attempts by campaign workers, who found clever ways around the system’s safeguards.

A coalition of parties accuses IBK’s camp of engaging in fraud, while Soumaïla Cissé’s party alleges that ballot-stuffing occurred. IBK’s rivals objected to Tuesday’s remarks by Col. Moussa Sinko Coulibaly, Mali’s interim minister of territorial administration, suggesting IBK would likely win an outright majority of votes, thus precluding a second round of voting. Coulibaly, whose ministry is charged with organizing elections and reporting the results, is no disinterested technocrat: he was chief of staff to junta leader Captain Amadou Sanogo prior to being named minister in April 2012. In light of IBK’s suspected links with the junta, the minister’s intervention struck many as inappropriate, possibly an attempt to curry favor with the likeliest winner or even manipulate the outcome.

The international community’s rush to sign off on Sunday’s vote was, perhaps, unseemly. But this election simply has to succeed, for many reasons. The Malian government needs a new president to begin the difficult process of getting the country out of its present crisis. The US needs an elected regime in Bamako with which to resume its bilateral aid and military assistance. And the French government needs to justify its risky strategy of the last several months, which forced Malian authorities to stick to a deadline they would have delayed if not for unrelenting French pressure. “For France, it is a great success,” Prime Minister Ayrault told the press. “Our international partners have hailed our courage and coherence because France in no way wanted to do anything reflecting the militarism and paternalism of the past, but on the contrary to give Africa and in this case Mali every chance to become a democratic independent nation, in charge of its own development.”

The bright side

However we might view such pronouncements, let’s give credit where it’s due: if Sunday’s vote was disorderly and shambolic, it was peaceful, and it was no disaster. The skeptics, including me, have so far been proven wrong. And the most promising aspect of Mali’s election story is that turnout was big. As Diakaridia Yossi wrote in the Bamako daily L’Indépendant, “Never in Malian memory has a presidential election succeeded in mobilizing so many people.” Over 3.5 million votes were cast, 40 percent more than the previous record set in 2007. Participation was certainly poor in some areas, especially Kidal, where voter intimidation may have been a factor. At the national level, though, the official turnout rate was 51.5 percent. Remember, participation in previous elections has never reached 40 percent. Given the obstacles mentioned above, half of eligible Malians actually managing to cast ballots is a giant leap forward.

By turning out massively to vote, Malians confounded the cynics, both in Mali and abroad, who called this election a “charade” meant to legitimize Mali’s occupation and subsequent partition, “the greatest masquerade in the political history of Françafrique,” and the instrument of Mali’s submission to foreign powers. Ordinary Malians clearly felt that they and their country had something to gain from voting.

Mali’s election is far from over, and significant challenges remain. Perhaps the greatest will be convincing the losers that this process was indeed free and fair. The counting and reporting of votes has hardly been transparent to this point; as one Malian put it, “Even if God himself validated these results, there are those who will say that God was bought off.” Assuming IBK wins, some in Bamako are wondering whether his image could suffer from the uncertainty hanging over this election’s outcome. Once his honeymoon with the Malian public ends, doubts about how he achieved his victory could very well multiply — a dynamic dubbed “ATT syndrome.” Let’s hope Mali doesn’t go down that road again.

Postscript, 7 August: Pollster Sidiki Guindo has released a brief summary of his most recent survey data (gathered 8-14 July), from which he extrapolates second round percentages for IBK and Cissé. Guindo predicts that the maximum share Cissé can obtain is 43 percent.

is only 45 years old and on his first run for office, but has the backing of Mali’s largest and most powerful political party, ADEMA. This party ruled the country from 1992 to 2002 and played a role in every government since. Dioncounda Traoré, the former speaker of parliament, was its presidential hopeful until last year’s coup; this year, as interim president, he’s barred from running, so ADEMA had to pick someone else. Anxious to dissociate their party from the past, ADEMA’s leaders went with Dembélé, a virtual unknown. This former mining engineer carries some baggage over and above his ADEMA affiliation: as a former top official of the ministry of mines, he was briefly

is only 45 years old and on his first run for office, but has the backing of Mali’s largest and most powerful political party, ADEMA. This party ruled the country from 1992 to 2002 and played a role in every government since. Dioncounda Traoré, the former speaker of parliament, was its presidential hopeful until last year’s coup; this year, as interim president, he’s barred from running, so ADEMA had to pick someone else. Anxious to dissociate their party from the past, ADEMA’s leaders went with Dembélé, a virtual unknown. This former mining engineer carries some baggage over and above his ADEMA affiliation: as a former top official of the ministry of mines, he was briefly  was seen as the “establishment candidate” when he ran as ADEMA’s candidate for president (and lost to Amadou Toumani Touré) in 2002. He subsequently founded his own party. Now 63, he is running a well-funded campaign. He has been a bitter opponent of the junta, which

was seen as the “establishment candidate” when he ran as ADEMA’s candidate for president (and lost to Amadou Toumani Touré) in 2002. He subsequently founded his own party. Now 63, he is running a well-funded campaign. He has been a bitter opponent of the junta, which

was a minister and prime minister under ATT, and for many Malians embodies the legacy of ATT’s decade in office. He was widely

was a minister and prime minister under ATT, and for many Malians embodies the legacy of ATT’s decade in office. He was widely  Wealthy and influential businessman, head of Mali’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry, active in economic, civil society, and political circles. Former VP of the Parti pour le Développement Economique et Social (PDES), which strongly backed ATT during his rule.

Wealthy and influential businessman, head of Mali’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry, active in economic, civil society, and political circles. Former VP of the Parti pour le Développement Economique et Social (PDES), which strongly backed ATT during his rule. Native of Bourem (Gao region) and the field’s lone female. Former Air Afrique union activist; now an outspoken parliamentarian and PDES member. Running independently since her party decided not to enter a candidate. Rose to global attention in 2012 by speaking out in the media against the Islamist and separatist rebel takeover.

Native of Bourem (Gao region) and the field’s lone female. Former Air Afrique union activist; now an outspoken parliamentarian and PDES member. Running independently since her party decided not to enter a candidate. Rose to global attention in 2012 by speaking out in the media against the Islamist and separatist rebel takeover. Joined President Konaré’s ADEMA party and headed three different ministries under Konaré between 1993 and 2000. Started his own party in 2003 after unsuccessful bid as ADEMA’s presidential candidate; chaired the West African Monetary Union (2004 – 11).

Joined President Konaré’s ADEMA party and headed three different ministries under Konaré between 1993 and 2000. Started his own party in 2003 after unsuccessful bid as ADEMA’s presidential candidate; chaired the West African Monetary Union (2004 – 11).

Pan-Africain pour la Liberté, la Solidarité et la Justice/

Pan-Africain pour la Liberté, la Solidarité et la Justice/ Former NASA astrophysicist and ex-head of Microsoft Africa; served as interim prime minister from April to December 2012; forced to resign by junta. Married to daughter of former President Moussa Traoré.

Former NASA astrophysicist and ex-head of Microsoft Africa; served as interim prime minister from April to December 2012; forced to resign by junta. Married to daughter of former President Moussa Traoré.

Foreign minister during ATT’s transitional government (1991 – 92). Founded PARENA in 1995; ran unsuccessfully for president in 2002 and 2007. Brokered the

Foreign minister during ATT’s transitional government (1991 – 92). Founded PARENA in 1995; ran unsuccessfully for president in 2002 and 2007. Brokered the  au Mali/

au Mali/

Koutiala native; served as President Konaré’s campaign director, then foreign minister, then prime minister (1994 – 2000). Left ADEMA to form his own party, then became speaker of the National Assembly (2002 – 07). A contender in the 2002 and 2007 presidential elections.

Koutiala native; served as President Konaré’s campaign director, then foreign minister, then prime minister (1994 – 2000). Left ADEMA to form his own party, then became speaker of the National Assembly (2002 – 07). A contender in the 2002 and 2007 presidential elections.

field’s youngest candidate; a Songhai with little name recognition, no strong party base and a skeletal website. His platform centers on appeals to youth voters and Pan-Africanism.

field’s youngest candidate; a Songhai with little name recognition, no strong party base and a skeletal website. His platform centers on appeals to youth voters and Pan-Africanism. Gao native who ran for president in 2002, then served as ATT’s minister of industry and commerce (2002 – 04). Backed ATT’s reelection in 2007.

Gao native who ran for president in 2002, then served as ATT’s minister of industry and commerce (2002 – 04). Backed ATT’s reelection in 2007.

l’indépendance/

l’indépendance/ economics from the University of Pittsburgh and has worked for the UN, the African Development Bank and the US Agency for International Development. Viewed by many as a solid technocrat during a stint as finance minister under President Traoré (1986 – 87), he was ATT’s prime minister during the 1991-92 transition to democracy, and made a short-lived presidential bid in 1997.

economics from the University of Pittsburgh and has worked for the UN, the African Development Bank and the US Agency for International Development. Viewed by many as a solid technocrat during a stint as finance minister under President Traoré (1986 – 87), he was ATT’s prime minister during the 1991-92 transition to democracy, and made a short-lived presidential bid in 1997. of the town of Ouéléssébougou; holds a master’s in public policy from BYU and is vice president of Mali’s League of Mayors. Best known abroad as “the Mormon candidate,” though his affiliation with the Church of Latter-Day Saints is generally ignored by the Malian press.

of the town of Ouéléssébougou; holds a master’s in public policy from BYU and is vice president of Mali’s League of Mayors. Best known abroad as “the Mormon candidate,” though his affiliation with the Church of Latter-Day Saints is generally ignored by the Malian press.

Deputy from Dioïla; ex-cabinet minister (1991 – 92). Split from PARENA this year to form his own party.

Deputy from Dioïla; ex-cabinet minister (1991 – 92). Split from PARENA this year to form his own party. l’Emergence, b. 1952) Former inspector-general of Mali’s national police; headed up the ministries of health and foreign affairs under President Konaré. Was ATT’s secretary-general of the presidency before becoming his prime minister (2007 – 11).

l’Emergence, b. 1952) Former inspector-general of Mali’s national police; headed up the ministries of health and foreign affairs under President Konaré. Was ATT’s secretary-general of the presidency before becoming his prime minister (2007 – 11).

Lawyer; founded CNID in 1991; placed 3rd in the 1992 presidential race. After boycotting the 1997 poll, ran again in 2002. Has represented the city of Ségou in Mali’s National Assembly since 2002.

Lawyer; founded CNID in 1991; placed 3rd in the 1992 presidential race. After boycotting the 1997 poll, ran again in 2002. Has represented the city of Ségou in Mali’s National Assembly since 2002. 1975) Another young hopeful with scant political experience and a fledgling party. Has a French business degree and worked most recently as communications director for Orange Mali, one of the country’s two cell phone networks.

1975) Another young hopeful with scant political experience and a fledgling party. Has a French business degree and worked most recently as communications director for Orange Mali, one of the country’s two cell phone networks.

Renouveau – Afriki Lakuraya/

Renouveau – Afriki Lakuraya/ Renouveau) Onetime ATT ally and adviser to the presidency; affiliated with the UK-based

Renouveau) Onetime ATT ally and adviser to the presidency; affiliated with the UK-based

One Hippopotamus and Eight Blind Analysts

One Hippopotamus and Eight Blind Analysts