Afrobarometer has recently released the results of a special opinion survey carried out across Mali between 17 December 2013 and 5 January 2014. This survey randomly sampled over 2000 Malians from each of the country’s nine regions and the District of Bamako, weighted in proportion to national population share. The findings (as detailed in Afrobarometer Policy Paper 9, “Mali’s Public Mood Reflects Newfound Hope,” and Afrobarometer Policy Paper 10, “Popular Perceptions of the Causes and Consequences of the Conflict in Mali“) suggest that Malians believe their country to be in a much better situation than it was a year ago, and that they are broadly confident that the country’s prospects will continue to improve.

Not surprisingly, most respondents (67 percent) told surveyors that Mali is headed in the right direction, compared to just 25 percent who had expressed the same opinion in December 2012. This opinion was even more commonly held by residents of northern regions and internally displaced persons in the recent poll, perhaps because they had emerged from Islamist occupation in early 2013.

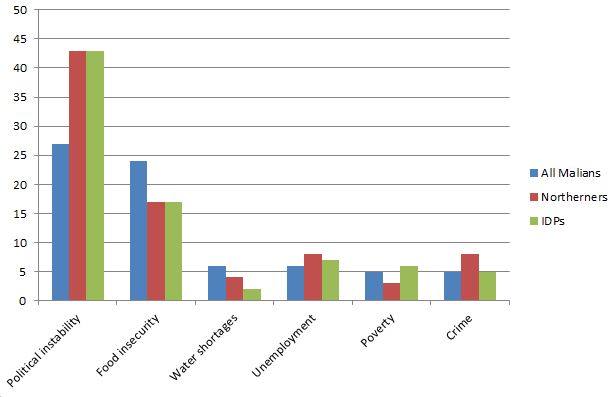

When asked to identify the most pressing problems to be addressed by the Malian government, Malians (especially northerners and the internally displaced) were most likely to cite political instability (see chart below). Food insecurity was a close second at the national level, but whereas 25 percent of southerners listed it as a priority, only 17 percent of northerners and IDPs did the same. Despite perceptions of northern Mali as a zone of chronic famine, hunger is a greater concern in the south than in the north. If this sounds implausible, remember that government studies in recent years (e.g. the 2011 ELIM survey) have found the country’s highest levels of poverty to be in the southern Sikasso region, where at least eight out of ten residents are considered poor.

In addition to their shared sense that Mali is on the right track, southerners and northerners have similar outlooks with regard to the restoration of security: 60 percent of respondents nationally believed that basic security would be restored by the end of 2014, and 71 percent of northerners agreed. Northerners, however, were more likely than southerners to report feeling unsafe in various contexts.

Although they mostly characterized their own economic situations as “fairly bad” or “very bad,” Malians appeared hopeful for their prospects: roughly nine out of ten believed their own economic conditions would improve in the coming year. They gave the Malian government poor marks for its handling of the economy, reducing poverty, creating jobs, stabilizing consumer prices, and lessening inequality. Yet 62 percent expressed confidence that it can solve these problems in the future.

With respect to Mali’s most recent armed conflict (late 2011-mid 2013), respondents were asked “How many of the following options can help resolve the conflict?” The choices were “A strong state,” “Render justice to all people involved,” “Civic education,” “Development of the northern regions,” “Dialogue between the State and armed groups,” and “Secession of the northern regions.” The Afrobarometer team showed that a strong state is favored throughout the country, particularly in the north. For the most part, northerners were more likely than Malians overall to cite northern development, but less likely to support dialog with rebels or even secession (see chart below).

Malians are split on the prospects of a negotiated peace agreement. Asked to assess the “probability that signing an agreement is the basis for sustainable peace in Mali,” significant minorities (24 percent nationally, and as high as 41 percent in Gao) answered that it was “not at all probable.” But most respondents were at least somewhat positive about such an outcome: 65 percent nation-wide rated is as either “a little probable” or “very probable.” For Kidal the figure was 67 percent (see chart below).

I take away two important conclusions from this survey. One, Malians are an optimistic lot: despite their own dismal circumstances, they tend to feel hopeful for the future. (Not at all like those melancholy Zambians studied by James Ferguson some years ago.) Two, Malians generally agree on the best responses to their country’s crisis: building a strong, capable state, putting an end to impunity, educating citizens, and developing the north are widely supported by the Malian public. Easier said than done, of course, but at least they favor the same options. Afrobarometer research has shown that northerners and southerners had different experiences of conflict and displacement since 2012, yet when it comes to the problems affecting the country and their potential solutions, the perceptions in the north and in the south are not terribly divergent. Perhaps there is reason to be hopeful for Mali’s future after all.

Postscript, 3 April: In light of news from Afrobarometer that a coding error had affected some of the data in their original tables on responses from northern Malians, I have updated this post to reflect revised figures. 17 percent of northerners listed food insecurity in Table 2 (not 15 percent as previously stated), and 71 percent of northerners believed that security would be restored by the end of 2014 (not 44 percent as previously stated). The results posted on the Afrobarometer website have also incorporated these revisions.

From the second report, it is interesting to see that in Dec. 2012, the highest # of respondents claimed “lack of patriotism of the leaders” was the principal cause for the occupation, but by 2013, it switched to “foreign terrorists.” I wonder if the French/international rhetoric identifying “terrorism” as the principal reason for the Jan. 2013 intervention had an impact on the change?