In ordering French troops to quit Malian soil “without delay,” Mali’s transitional authorities are making a high-stakes wager.

Their bet seems to be that whatever price the evacuation of Operation Barkhane imposes on Malians in the short term, it will be more than offset by the free hand the government will gain to set its own security policy and control its own territory. This is a risky bet, and the challenges ahead are many.

Without accompaniment (or interference, depending on your perspective) by French and other foreign troops, Malian soldiers must quell the jihadi insurgency ravaging the country’s northern and central regions. Given a free hand and Russian support, perhaps they can force the jihadis to the bargaining table. The Malian government has mulled such talks for years but France always opposed them (falling back on the “no negotiating with terrorists” mantra). If and when negotiations happen, Mali’s 62-year-old doctrine of state secularism could become a bargaining chip: establishing Islamic law is the jihadis’ top demand. Are Malian politicians willing to put laïcité on the table?

At the time time, the government must begin the long-delayed overhaul of state institutions and map out an eventual return to civilian rule. Ordinary Malians have little faith in Mali’s previous, nominally democratic system to deliver anything but more of the same – corruption, lack of opportunity, and rising inequality.

This process of refondation must also entail addressing demands by restive Tuareg groups. Since the Algiers Accord was signed in 2015, there’s been very little progress in resolving longstanding disagreements over the concentration of state power and how best to represent Tuareg communities (particularly the trouble-making, high-status clans) within the national political framework. This deadlock was the subject of a recent meeting in Rome.

Economically speaking, the Malian government may need to find new partners abroad. 50% of its budget has been funded by donors, largely the European Union and EU member states. If these donors curtail or reduce their aid, as some have already done, will any others (perhaps emerging partners like Turkey and Iran) step in to fill the void? Or will Malian authorities seek a new business model less dependent on foreign largess?

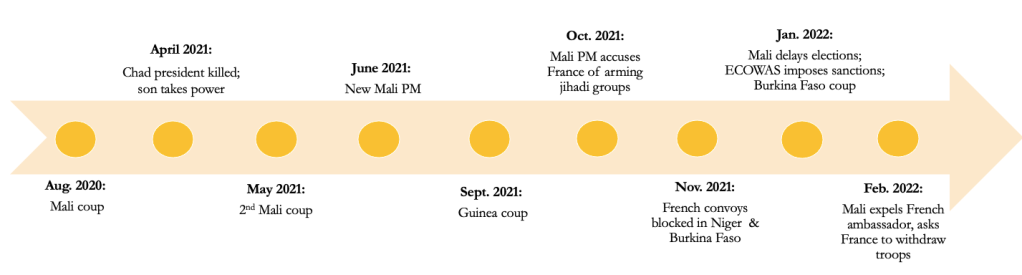

The last several months have been incredibly eventful in Mali and the region (see timeline above). I could scarcely have imagined this series of developments just a year and a half ago (Mali expelled whose ambassador? Mali kicked out whose military force?). After a series of coups and a dramatic rebalancing of international alliances throughout West Africa, the international liberal project of market-driven policy reforms and democratic elections is looking like it’s on life support, a victim partly of the low ebb in Franco-African relations and partly of its own contradictions. If the liberalism project dies, what might replace it?

These are all daunting challenges, even without mentioning looming threats from climate change, food insecurity, or demographic pressure. The most hopeful sign, however, is that Mali’s transitional authorities seem to have found a new national narrative to replace the “good pupil of liberalism” narrative that fell apart a decade ago. Undoubtedly, Mali lost the plot under the late President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita. There was no compelling story to unite the population or mobilize public support. Standing up to France and the “international community” (the US, EU, UN, ECOWAS, and other pillars of the liberal post-Cold War order) has become a huge source of pride for many in Mali, not to mention elsewhere. “The Mali that can say no,” that sacrifices old exploitative alliances in hopes of securing more equitable ones, projects a renewed sense of national purpose. It prompts its citizens to consider the sacrifices they can make in turn.

It has been inspiring to watch Foreign Minister Abdoulaye Diop tell this story on Mali’s behalf to the world. Where most of his predecessors maintained low profiles, he has chosen to take his government’s case about the necessity of asserting sovereignty to a global audience. Not content with frequenting the usual media outlets (RFI, France 24) alone, he recently gave an extended interview to Al Jazeera (English and Arabic). He struck an effective balance between diplomatic restraint and passionate defense of his government’s plans.

These are dangerous but heady times. Previously all-but-unthinkable prospects are beginning to materialize. Could Mali abandon the CFA Franc zone (as it did once before, during the 1960s)? If it does, will other West African states follow its lead? What would it mean for the Malian government to forge relations with governments of the Global North (including the French government) on equitable terms — with respect for national sovereignty as the first imperative, and with Mali being more than a theater where superpowers demonstrate their political and military clout, or a laboratory for European armies to test their counter-insurgency tactics?

Perhaps this new phase of Franco-African relations and its prospects for transformation will prove short-lived. Perhaps hopes for a new postcolonial dispensation are unrealistic. But I, for one, fervently hope that Mali’s gamble for sovereignty pays off.

This is all akin to climbing Mt. Everest in the middle of winter.

Forgive my cynicism, but I have been waiting for French Soudan/Mali to take its rightful place on the world stage for 73 years. Hope comes; hope fades. Tout change sauf les Africains.

Avec le plus profond respect pour les Malien.nes qui m’on instruit depuis les 1990s, je craint toujours un nationalisme ancré sur les intérêts politico-économiques au sud du pays et centré le ‘Maliba’ Mande/ Bamanankan. L’inclusion des préoccupations des populations des ‘régions’ nécessite aussi une épopée nationale transformée a côté d’un état refondé. Peut-être sont émergents des imaginations à la hauteur des imaginaires nécessaires?

Je trouve cette crainte tout à fait justifiée… et j’espère que les imaginations seront bien à la hauteur !

I also listened to/viewed your Lehigh University conference of last Friday, 18th. I can understand that Malians now reject French military support/interventions; because of lack of impact, for instance. But what are your arguments for stating that Malians also dismiss “the international liberal project of market-driven policy reforms and democratic elections [is looking like it’s on life support]”?

Good question. I wouldn’t say that Malians dismiss the international liberal project altogether, but I do think that many Malians have grown wary of the project’s proponents, especially considering the project’s failure to deliver the promised goods (accountable elites, responsive institutions, a just dispensation of the benefits of economic growth) over the years. They don’t believe the French govt. when it says it claims to want a legitimately elected regime in Bamako (since France didn’t insist on one in N’Djamena), and they don’t believe ECOWAS when it claims to care about Malian democracy (since many ECOWAS heads of state have minimal democratic credentials at best). PM Maiga’s insistence that ECOWAS sanctions are “illegal” is his attempt to delegitimize the primary tool (or weapon) used in the name of international liberalism to persuade states to follow the liberal democratic playbook.

Thank you. It is good to hear from someone who is seeing what I’m seeing and hoping for what I’m hoping for. I’ve been dealing with the police and justice system lately. I’m seeing how the people make use of a system that pretends to be something it’s not too accomplish the behavior change it is meant to produce. All the same, I believe they could operate more successfully without the mask and the lies. When a system of people is already deep in the habit of making a living deceptively…I think it has to die out completely before it can be resurrected to new life. Based on what I know about my neighbors those could be dark, lawless days, and the quickest return to order seems to be Sharia. I do love the Malian people. That’s why I give my all for their best.

I find Foucault’s “authorless strategies” useful for understanding these processes–the outcomes are not necessarily what the “planners” were seeking, yet they serve certain interests all the same.

Yes. That is helpful. I wouldn’t say “Authorless” because I know the Author, but that really helps frame what I’m seeing in Mali. Just now your title struck me. “Betting Big on Sovereignty”…that’s exactly how I live.

Since you know the Author, could you get me an autographed copy? 🙂

https://www.dw.com/en/malians-suffer-under-strain-of-economic-sanctions/av-61182123