Fifteen years ago this month, I came to Bamako for the very first time. In those days I was a fresh-faced Peace Corps trainee, more eager to get out to my rural post than to experience the city. On the bus from the airport, I remember being saddened by the sight of open sewers and corrugated metal roofs.

When I returned to Bamako several months later, I saw it with new eyes. Rather than comparing it to the American cities I knew, I compared it to the rural Malian communities I knew, where corrugated metal roofs are a sign of prosperity (they last longer than thatch), and sewers of any kind simply don’t exist, so seasonal rains cause flooding and erosion. At least Bamako had sewers, not to mention electricity — even if neither worked properly much of the time. And the city boasted other amenities, such as restaurants and spaces for leisure, that I came to appreciate more over time.

Since my Peace Corps service ended in 2000 I’ve returned to Bamako every couple of years, and have been struck by the city’s transformation. I’ve come to see Bamako as a kind of urbanization laboratory. In some ways life for Bamakois today seems better than before; in other ways it’s more difficult. Here I’ll use the occasion of this 15-year anniversary to reflect on several changes the city of Bamako has seen since the close of the 20th century.

Demographic growth: By any measure, Bamako’s population has been expanding at breakneck speed. According to the City Mayors Foundation, Bamako’s annual growth rate is 4.45%, which makes it the sixth-fastest-growing city in the world, and the fastest on the African continent. The city’s population attained the one million mark only in 1998, and by 2010 it had exceeded two million.

The city’s expansion is also spatial — largely horizontal rather than vertical. The ACI 2000 neighborhood, allotted twelve years ago on the former site of a military air base just west of downtown, now houses many of Bamako’s government offices and embassies. And whole new neighborhoods are springing up on the edge of town, in places like Kalaban-Coro Heremakono, Boulkassoumbougou and Doumanzana, where five or six years ago you could only find mango groves and scrub brush. Today they’re home to thousands of cinder-block homes, most of them unfinished but nonetheless occupied.

Traffic jams: As the city grows, and as increasing numbers of its residents can afford cars and motorcycles, more and more people occupy Bamako’s road-ways. In the 1990s, heavy traffic was rare in Bamako, and there were just two or three areas downtown where the sheer volume of vehicles caused delays. Now embouteillages are nearly constant from the Route de Koulikoro to Niaréla to the Grand Marché to Lafiabougou. The two main bridges across the Niger River are major choke points seven days a week. “Nowhere near as bad as the ‘go-slows’ in Lagos,” Nigerians might say, but really, this is hardly something to boast about.

Mobile telephony: In 1997 there was no cellular service anywhere in Mali. By 2000, a few wealthy Bamakois had cell phones. Now, 91% of Bamako households own at least one cell phone, according to the ELIM survey published by the Malian government last year. It would be difficult to overstate the impact of this technology on urban social life. In the old days, if you wanted to meet people, you often had to go to their home or office and hope they’d be in. Land-line phones were expensive and unreliable. Now, with your cell phone, you can coordinate with almost anyone, at almost any time, via voice or SMS (that’s “text messages” to you ignorant Yanks).

An emerging consumer class: Wherever you look, there’s evidence of the growing number of Bamakois who have risen to middle-class status. They drive more, watch more TV (and more channels: Bamako has four broadcast channels now, compared to two in 2000). They spend an increasing amount on leisure, as demonstrated by the host of extravagant New Years soirées advertised on TV, for which tickets cost from 25,000 to 50,000 CFA francs (US$50-$100!). And they buy consumer goods they never used to buy. One example is disposable diapers: until recently, these were hugely expensive and purchased exclusively in fancy supermarkets by expat parents. Nowadays, cheap diapers are sold by market women and street hawkers to a local clientele. Then you’ve got new forms of conspicuous consumption: throughout Africa, for instance, a German firm is marketing an energy![]() drink known as “Bizz’up” made from hibiscus flowers. This name, familiar to those who’ve been to West Africa, is ripped off from bissap, a hibiscus drink that’s locally made. Why would Malians want to drink an expensive imported version of something produced cheaply right here at home? Because they can. (But I still think it’s both silly and deeply wrong.)

drink known as “Bizz’up” made from hibiscus flowers. This name, familiar to those who’ve been to West Africa, is ripped off from bissap, a hibiscus drink that’s locally made. Why would Malians want to drink an expensive imported version of something produced cheaply right here at home? Because they can. (But I still think it’s both silly and deeply wrong.)

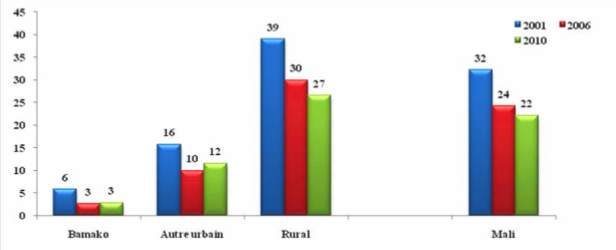

Development: The most recent ELIM survey is full of interesting figures, most of them encouraging, about social and economic development in Mali and in Bamako. If you believe these government figures, in 2010, for instance, 98% of Bamako households had access to potable water, and 70% had electricity (this latter figure had nearly doubled since 2001). Three-quarters of children in Bamako attended primary school, up from 58% in 2001. Moreover, the proportion of Bamakois living in poverty had dropped from 17.6% in 2001 to 9.6% in 2010, while the proportion of those living in extreme poverty was cut in half, from 6% to 3% over the same period. Has Bamako achieved that elusive goal, pro-poor economic growth?

Maybe. But this report also provides several discouraging signs. Many of the gains of the first decade of the 21st century were concentrated in the first five years, with stagnation or even regression from 2006 to 2010 in areas like poverty reduction (see chart below). Bamako saw no improvement in access to electricity, for example, after 2006; more disturbingly, the school enrollment figure actually dropped 10% from 2006 to 2010. Which brings us to what’s probably the most significant negative change of the last fifteen years.

The political mood: In the late 1990s, Mali was brimming with optimism. The country had recently emerged from decades of military dictatorship and had managed a transition to democratic rule that was hailed as a model for Africa. One sensed that Malians saw brighter days ahead, that while their country was extremely poor, at last it was headed in the right direction. I don’t get this sense here so much these days. Despite all the gains described above, I’m more likely to hear Malians voice frustration and disgust with inept public administration, rampant corruption, and a lack of leadership from their government.

Probably the most troubling area is the state of Malian public education. Remember that 10% drop in Bamako’s primary school enrollments from 2006 to 2010? Public schools have been so plagued by strikes and shut-downs that some families don’t see the point of sending their children to school anymore. This problem exists at all levels of the education apparatus, right up to the Universities of Bamako, where I’m supposed to be teaching. The whole university system has been closed since last July, pending organizational restructuring, and there’s been no word on when it will reopen. Thanks to Bamako’s increasing population — which owes as much to high fertility as to rural-to-urban migration — the strain on the city’s public schools is growing worse every year. Many Bamakois will tell you their political leaders simply aren’t interested in improving public education, since they all send their children to private schools.

At the core of the matter, of course, is politics: lots of Malians think the country’s politicians are sacrificing future generations for their own selfish interests. Americans may be cynical about their government, but at least U.S. public schools are open for business, and we trust the police to do their jobs. A growing number of Bamakois have lost faith in their government’s ability to do anything, from keeping the schools open to keeping criminals off the street. Some have begun dispensing mob justice to suspected thieves instead of turning them over to the police. And nothing’s likely to improve before elections are held in April.

What’s the upshot? Two words: fundamentally ambiguous. We may be encouraged by the progress made, but we should also be worried about the shortfalls. While Bamakois can take pride in their collective achievements of the last 15 years, pressing problems — many of them linked to explosive demographic growth — threaten those achievements and have already reversed some of the improvements of the early 2000s. Mali’s status as a role model of democratic transition mustn’t blind us to simmering discontent with the country’s democratic process, which more and more Malians associate with gridlock and anarchy.

What will the next 15 years bring? All I can say at this point is that most Malians aren’t expecting that the road ahead will become much smoother for them. At least for the next few years, the signs suggest the road will get rockier and steeper. And they will continue to toil onward, in spite of everything.

Bruce

Thanks for update on Mali. Well written and thorough as always. Colleen is now facebook friends with Mbe, that speaks volumes a out the changes in Mali. We would love to visit, but are waiting for when the kids can remember it.

“Americans may be cynical about their government, but at least U.S. public schools are open for business.” We’re certainly right to be cynical, and maybe American kids would be better off if U.S. schools weren’t open for business.

Ah, a predictably right-wing rant from my older bro. But this is not the place for a debate on the value of public education.

Bruce,

Thanks for the update, this is great insight into the changes in Bamako. Can you give us all a POV of the rural changes occurring as well? Glad to hear you are well and enjoying Mali still, I miss it very much. Warren Rider

Unfortunately I’m trapped in this city! Well not really, but for a number of reasons it’s difficult for me to get outside Bamako. In five months I have not yet been to my old Peace Corps post in the Sikasso region, nor even to the city of Sikasso. I did manage a two-day trip to the Siby area earlier this month, and a two-day trip to Segou over the weekend, but I won’t venture to assess the state of rural Malian life based on those two visits.

Thanks so much for this post – provided interesting insight into a place I’m always taking my students to in stories. This gave data for them to compare on other than levels than just Ms. Currie’s “When I was in Mali..” flashbacks.

This is a very nice article and I have asked myself the same question. What has changed ? You are giving some very interesting information. Thank you !

Thanks! Since writing this post I remembered one positive change I’d neglected to mention: the electrical supply is much more reliable than it used to be. Blackouts were daily in Bamako in the late 1990s, but since the Manantali Dam came on line they are few and far between. The few we’ve had since August (perhaps 10?) have lasted an average of 20 minutes, I’d say. I just hope this holds true during the hot season as well, which is just now getting underway.

Pingback: The Coup, Day Four | Bridges from Bamako

So prescient, given recent events: “Mali’s status as a role model of democratic transition mustn’t blind us to simmering discontent with the country’s democratic process.” Thank you, Bruce, for allowing me to reconnect to the beloved country of Mali I left as a PCV in 1993. A fantastic blog!

I’ve been thinking back to this post a lot since the coup. But it’s not so much a case of prescience as simply having listened to what Bamakois around me were saying about their government and their lives.

Bruce:

I began to follow your blog when I was searching for information about the current events that have blighted Mali’s political and hence developmental future. Thanks so much for your ongoing commentary about the current situation. But I’ve really enjoyed your older posts, including this one, that have provided a lot of perspective for a former PCV from the 1970s, who couldn’t imagine television, potable water, reliable electricity, or traffic jams anywhere in Mali. Many thanks for your good work and stay safe.

Pingback: On the Ground in Bamako: What’s next for Mali? | CONSTRUCTION

Pingback: Mali’s coup, one year on | Bridges from Bamako